Designing Human Interfaces – Interface Design and the User Experience

December 6, 2016 By Chad McComsey, aka TheChad

While attending the most recent WordCamp US in Philadelphia this month, I had the opportunity to hear a talk given by Tammie Lister (@karmatosed) called, “Design for humans not robots”. I was certainly intrigued by the title and thought it was an excellent place to start my WordCamp experience. My initial interpretation of the title wasn’t too far off and while I believed I had already gained a solid grasp of User Interface Design, I learned that there is a lot more to the concept of “Designing for Humans” than meets the eye. (insert Transformers joke here)

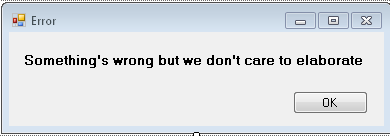

I believe the underlying thought was that of not designing interfaces for the systems we have all come to know. For example: we’re all aware of the look and feel of an alert pop-up or an error message; these are so common that it’s easy to consider them legitimately “good” design. The truth is that they are not. In actuality, they are cold, predetermined scripts and functions that are frustrating and remove any conception of human interaction. So how does one deal with this issue?

Understand How People Interact with the Experience

Without delving into psycho-babble and confusing rhetoric, the answer, is: “Understand how humans interact and react at a base level”. When an error screen pops up and all I see is a string of code and an error number, my reaction is, “What the hell does that mean?”. I’m not a developer so errors of this nature do nothing but confuse me and it’s in those moments that I feel the most separated from the experience as a user. Typically I will search for the answer and hopefully find one that makes sense even though it may mean I need help outside of the experience itself.

This concept echoes in many aspects of User Interface Design. Having a title that a user can understand and connect with, having meaningful calls to action, having well-thought-out navigation and form elements are important to a solid user experience and they all bring the user closer rather than push them away. Generally, if it makes a user go, “Huh?” “What the?” or “Why the heck?” – it’s likely not very effective.

Be a User, Not a Designer

The best thing designers can do when dealing with UI/UX is separate themselves from “design brain” and become a user. This might be a little difficult for some people who are more “tech savvy” and base their interface design on their own experiences but it’s well worth the effort. While there is nothing wrong with designing from experience, it’s actually a good exercise, it does tend to cut out the majority of users who are not as savvy or do not have the same experiences.

The best thing designers can do when dealing with UI/UX is separate themselves from “design brain” and become a user. This might be a little difficult for some people who are more “tech savvy” and base their interface design on their own experiences but it’s well worth the effort. While there is nothing wrong with designing from experience, it’s actually a good exercise, it does tend to cut out the majority of users who are not as savvy or do not have the same experiences.

During Tammie’s talk, I picked up the idea of focusing on “wanting to use and not having to use”. The user’s experience should allow for emotional connections, it shouldn’t confuse them or create stress. It should help them if they find themselves “stuck”. This makes your interface and experience more human and less robotic or artificial.

Respect Your Users, Be Realistic

Another way to keep your interface design human is to simply be realistic. Know who you are designing for and use that information to guide your tests. Whether it’s your tech-savvy child or your “never touched a computer in her life” grandmother, all of the info that is pertinent to that segment will highlight your path. It should go without saying that we are all different. No two user bases will benefit equally from the same design. If you rely on the constant that “states change with age” – both technically and physiologically – you’ll soon realize that there is no “all-in-one” solution for user interface design.

Conceptually, we’re all trying to simplify things for users and get them where they need in the fewest steps. Understanding how states change will effectively outline some essential factors that need to be considered even before pen meets paper. When you put your users first with the goal of creating a bond and helping them be the best user they can be, not only are you showing that you understand them but that you also respect them.

View Comments